|

Static and Kinetic Frictional Forces |

|

|

When an object is in contact with a surface, there is a force acting on the object. The previous section discusses the component

of this force that is perpendicular to the surface, which is called the normal force. When the object moves or attempts to

move along the surface, there is also a component of the force that is parallel to the surface. This parallel force component

is called the frictional force, or simply friction.

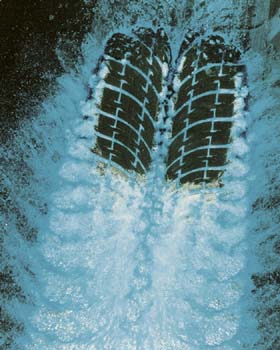

In many situations considerable engineering effort is expended trying to reduce friction. For example, oil is used to reduce

the friction that causes wear and tear in the pistons and cylinder walls of an automobile engine. Sometimes, however, friction

is absolutely necessary. Without friction, car tires could not provide the traction needed to move the car. In fact, the raised

tread on a tire is designed to maintain friction. On a wet road, the spaces in the tread pattern (see Figure

4.18) provide channels for the water to collect and be diverted away. Thus, these channels largely prevent the water from coming

between the tire surface and the road surface, where it would reduce friction and allow the tire to skid.

|

|

|

|

|

| Courtesy Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4.18 |

This photo, shot from underneath a transparent surface, shows a tire rolling under wet conditions. The channels in the tire

collect and divert water away from the regions where the tire contacts the surface, thus providing better traction.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure

4.20 helps to explain the main features of the type of friction known as

static friction. The block in this drawing is initially at rest on a table, and as long as there is no attempt to move the block, there is

no static frictional force. Then, a horizontal force

is applied to the block by means of a rope. If

is small, as in part

a, experience tells us that the block still does not move. Why? It does not move because the static frictional force

exactly cancels the effect of the applied force. The direction of

is opposite to that of

, and the magnitude of

equals the magnitude of the applied force,

fs =

F. Increasing the applied force in Figure

4.20 by a small amount still does not cause the block to move. There is no movement because the static frictional force also increases

by an amount that cancels out the increase in the applied force (see part

b of the drawing). If the applied force continues to increase, however, there comes a point when the block finally “breaks

away” and begins to slide. The force just before breakaway represents the

maximum static frictional force

that the table can exert on the block (see part

c of the drawing). Any applied force that is greater than

cannot be balanced by static friction, and the resulting net force accelerates the block to the right.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4.20 |

Applying a small force  to the block, as in parts a and b, produces no movement, because the static frictional force to the block, as in parts a and b, produces no movement, because the static frictional force  exactly balances the applied force. (c) The block just begins to move when the applied force is slightly greater than the maximum static frictional force exactly balances the applied force. (c) The block just begins to move when the applied force is slightly greater than the maximum static frictional force  . .

|

|

|

|

|

Experimental evidence shows that, to a good degree of approximation, the maximum static frictional force between a pair of

dry, unlubricated surfaces has two main characteristics. It is independent of the apparent macroscopic area of contact between

the objects, provided that the surfaces are hard or nondeformable. For instance, in Figure

4.21 the maximum static frictional force that the surface of the table can exert on a block is the same, whether the block is

resting on its largest or its smallest side. The other main characteristic of

is that its magnitude is proportional to the magnitude of the normal force

. As Section

4.8 points out, the magnitude of the normal force indicates how hard two surfaces are being pressed together. The harder they

are pressed, the larger is

, presumably because the number of “cold-welded,” microscopic contact points is increased. Equation

4.7 expresses the proportionality between

and

FN with the aid of a proportionality constant μ

s, which is called the

coefficient of static friction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4.21 |

The maximum static frictional force  would be the same, no matter which side of the block is in contact with the table. would be the same, no matter which side of the block is in contact with the table.

|

|

|

|

|

It should be emphasized that Equation

4.7 relates only the

magnitudes of

and

,

not the vectors themselves. This equation does not imply that the directions of the vectors are the same. In fact,

is parallel to the surface, while

is perpendicular to it.

The coefficient of static friction, being the ratio of the magnitudes of two forces

, has no units. Also, it depends on the type of material from which each surface is made (steel on wood, rubber on concrete,

etc.), the condition of the surfaces (polished, rough, etc.), and other variables such as temperature. Table

4.2 gives some typical values of μ

s for various surfaces. Example

9 illustrates the use of Equation

4.7 for determining the maximum static frictional force.

|

|

| Table 4.2 |

Approximate Values of the Coefficients of Friction for Various Surfaces1

|

|

Materials

|

Coefficient of Static Friction, μs

|

Coefficient of Kinetic Friction, μk

|

|

Glass on glass (dry)

|

0.94

|

0.4

|

|

Ice on ice (clean, 0 °C)

|

0.1

|

0.02

|

|

Rubber on dry concrete

|

1.0

|

0.8

|

|

Rubber on wet concrete

|

0.7

|

0.5

|

|

Steel on ice

|

0.1

|

0.05

|

|

Steel on steel (dry hard steel)

|

0.78

|

0.42

|

|

Teflon on Teflon

|

0.04

|

0.04

|

|

Wood on wood

|

0.35

|

0.3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Analyzing Multiple-Concept Problems |

|

|

|

|

|

Example

9

The Force Needed To Start a Skier Moving

|

A skier is standing motionless on a horizontal patch of snow. She is holding onto a horizontal tow rope, which is about to

pull her forward (see Figure 4.22a). The skier's mass is 59 kg, and the coefficient of static friction between the skis and snow is 0.14. What is the magnitude

of the maximum force that the tow rope can apply to the skier without causing her to move?

Knowns and Unknowns

The data for this problem are as follows:

|

|

|

Description

|

Symbol

|

Value

|

|

Mass of skier

|

m

|

59 kg

|

|

Coefficient of static friction

|

μs

|

0.14

|

|

Unknown Variable

|

|

|

|

Magnitude of maximum horizontal force that tow rope can apply

|

F

|

?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Newton's Second Law (Horizontal Direction) Newton's Second Law (Horizontal Direction) Figure 4.22a shows the two horizontal forces that act on the skier just before she begins to move: the force  applied by the tow rope and the maximum static frictional force  . Since the skier is standing motionless, she is not accelerating in the horizontal or x direction, so ax = 0 m/s 2. Applying Newton's second law (Equation 4.2a) to this situation, we have

Since the net force Σ Fx in the x direction is  , Newton's second law can be written as  . Thus,

We do not know  , but its value will be determined in Steps 2 and 3.

|

|

The Maximum Static Frictional Force The Maximum Static Frictional Force The magnitude  of the maximum static frictional force is related to the coefficient of static friction μ s and the magnitude FN of the normal force by Equation 4.7:

We now substitute this result into Equation 1, as indicated in the right column. The coefficient of static friction is known,

but FN is not. An expression for FN will be obtained in the next step.

|

|

Newton's Second Law (Vertical Direction) Newton's Second Law (Vertical Direction) We can find the magnitude F N of the normal force by noting that the skier does not accelerate in the vertical or y direction, so ay = 0 m/s 2. Figure 4.22b shows the two vertical forces that act on the skier: the normal force  and her weight  . Applying Newton's second law (Equation 4.2b) to the vertical direction gives

The net force in the y direction is Σ Fy = + FN - mg, so Newton's second law becomes +F N - mg = 0. Thus,

We now substitute this result into Equation 4.7, as shown at the right.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Solution

Algebraically combining the results of the three steps, we have

The magnitude F of the maximum force is

If the force exerted by the tow rope exceeds this value, the skier will begin to accelerate forward.

|

|

|

Related Homework: Problems 44, 108, 118 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Once two surfaces begin sliding over one another, the static frictional force is no longer of any concern. Instead, a type

of friction known as

kinetic* friction comes into play. The kinetic frictional force opposes the relative sliding motion. If you have ever pushed an object across

a floor, you may have noticed that it takes less force to keep the object sliding than it takes to get it going in the first

place. In other words, the kinetic frictional force is usually less than the static frictional force.

Experimental evidence indicates that the kinetic frictional force

has three main characteristics, to a good degree of approximation. It is independent of the apparent area of contact between

the surfaces (see Figure

4.21). It is independent of the speed of the sliding motion, if the speed is small. And lastly, the magnitude of the kinetic frictional

force is proportional to the magnitude of the normal force. Equation

4.8 expresses this proportionality with the aid of a proportionality constant μ

k, which is called the

coefficient of kinetic friction.

Equation

4.8, like Equation

4.7, is a relationship between only the magnitudes of the frictional and normal forces. The directions of these forces are perpendicular

to each other. Moreover, like the coefficient of static friction, the coefficient of kinetic friction is a number without

units and depends on the type and condition of the two surfaces that are in contact. As indicated in Table

4.2, values for μ

k are typically less than those for μ

s, reflecting the fact that kinetic friction is generally less than static friction. The next example illustrates the effect

of kinetic friction.

|

|

|

Analyzing Multiple-Concept Problems |

|

|

|

|

|

Example

10

Sled Riding

|

A sled and its rider are moving at a speed of 4.0 m/s along a horizontal stretch of snow, as Figure 4.24a illustrates. The snow exerts a kinetic frictional force on the runners of the sled, so the sled slows down and eventually

comes to a stop. The coefficient of kinetic friction is 0.050. What is the displacement x of the sled?

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4.24 |

|

|

(a)

|

The moving sled decelerates because of the kinetic frictional force.

|

|

|

(b)

|

Three forces act on the moving sled, the weight  of the sled and its rider, the normal force  , and the kinetic frictional force  . The free-body diagram for the sled shows these forces.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Knowns and Unknowns

The data for this problem are listed in the table:

|

|

|

Description

|

Symbol

|

Value

|

Comment

|

|

Explicit Data

|

|

|

|

|

Initial velocity

|

v0x

|

+4.0 m/s

|

Positive, because the velocity points in the +x direction. See drawing.

|

|

Coefficient of kinetic friction

|

μk

|

0.050

|

|

|

Implicit Data

|

|

|

|

|

Final velocity

|

vx

|

0 m/s

|

The sled comes to a stop.

|

|

Unknown Variable

|

|

|

|

|

Displacement

|

x

|

?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Displacement Displacement To obtain the displacement x of the sled we will use Equation 3.6a from the equations of kinematics:

Solving for the displacement x gives the result shown at the right. This equation is useful because two of the variables, v0x and vx, are known and the acceleration ax can be found by applying Newton's second law to the accelerating sled (see Step 2).

|

|

Newton's Second Law Newton's Second Law Newton's second law, as given in Equation 4.2a, states that the acceleration ax is equal to the net force Σ Fx divided by the mass m:

The free-body diagram in Figure 4.24b shows that the only force acting on the sled in the horizontal or x direction is the kinetic frictional force  . We can write this force as - fk, where fk is the magnitude of the force and the minus sign indicates that it points in the - x direction. Since the net force is Σ Fx = - fk, Equation 4.2a becomes

This result can now be substituted into Equation 1, as shown at the right.

|

|

Kinetic Frictional Force Kinetic Frictional Force We do not know the magnitude fk of the kinetic frictional force, but we do know the coefficient of kinetic friction μ k. According to Equation 4.8, the two are related by

where FN is the magnitude of the normal force. This relation can be substituted into Equation 2, as shown at the right. An expression

for FN will be obtained in the next step.

|

|

Normal Force Normal Force The magnitude FN of the normal force can be found by noting that the sled does not accelerate in the vertical or y direction ( ay = 0 m/s 2). Thus, Newton's second law, as given in Equation 4.2b becomes

There are two forces acting on the sled in the y direction, the normal force  and its weight  [see part (b) of the drawing]. Therefore, the net force in the y direction is

where W = mg (Equation 4.5). Thus, Newton's second law becomes

This result for FN can be substituted into Equation 4.8, as shown at the right.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Solution

Algebraically combining the results of each step, we find that

Note that the mass m of the sled and rider is algebraically eliminated from the final result. Thus, the displacement of the sled is

|

|

|

Related Homework: Problems 48, 49, 85 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Static friction opposes the impending relative motion between two objects, while kinetic friction opposes the relative sliding

motion that actually does occur. In either case,

relative motion is opposed. However, this opposition to relative motion does not mean that friction prevents or works against the motion

of

all objects. For instance, the foot of a person walking exerts a force on the earth, and the earth exerts a reaction force on

the foot. This reaction force is a static frictional force, and it opposes the impending backward motion of the foot, propelling

the person forward in the process. Kinetic friction can also cause an object to move, all the while opposing relative motion,

as it does in Example

10. In this example the kinetic frictional force acts on the sled and opposes the relative motion of the sled and the earth.

Newton's third law indicates, however, that since the earth exerts the kinetic frictional force on the sled, the sled must

exert a reaction force on the earth. In response, the earth accelerates, but because of the earth's huge mass, the motion

is too slight to be noticed.

|

| Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. |

is applied to the block by means of a rope. If

is applied to the block by means of a rope. If  is small, as in part a, experience tells us that the block still does not move. Why? It does not move because the static frictional force

is small, as in part a, experience tells us that the block still does not move. Why? It does not move because the static frictional force  exactly cancels the effect of the applied force. The direction of

exactly cancels the effect of the applied force. The direction of  is opposite to that of

is opposite to that of  , and the magnitude of

, and the magnitude of  equals the magnitude of the applied force, fs = F. Increasing the applied force in Figure 4.20 by a small amount still does not cause the block to move. There is no movement because the static frictional force also increases

by an amount that cancels out the increase in the applied force (see part b of the drawing). If the applied force continues to increase, however, there comes a point when the block finally “breaks

away” and begins to slide. The force just before breakaway represents the maximum static frictional force

equals the magnitude of the applied force, fs = F. Increasing the applied force in Figure 4.20 by a small amount still does not cause the block to move. There is no movement because the static frictional force also increases

by an amount that cancels out the increase in the applied force (see part b of the drawing). If the applied force continues to increase, however, there comes a point when the block finally “breaks

away” and begins to slide. The force just before breakaway represents the maximum static frictional force  that the table can exert on the block (see part c of the drawing). Any applied force that is greater than

that the table can exert on the block (see part c of the drawing). Any applied force that is greater than  cannot be balanced by static friction, and the resulting net force accelerates the block to the right.

cannot be balanced by static friction, and the resulting net force accelerates the block to the right.

is that its magnitude is proportional to the magnitude of the normal force

is that its magnitude is proportional to the magnitude of the normal force  . As Section 4.8 points out, the magnitude of the normal force indicates how hard two surfaces are being pressed together. The harder they

are pressed, the larger is

. As Section 4.8 points out, the magnitude of the normal force indicates how hard two surfaces are being pressed together. The harder they

are pressed, the larger is  , presumably because the number of “cold-welded,” microscopic contact points is increased. Equation 4.7 expresses the proportionality between

, presumably because the number of “cold-welded,” microscopic contact points is increased. Equation 4.7 expresses the proportionality between  and FN with the aid of a proportionality constant μs, which is called the coefficient of static friction.

and FN with the aid of a proportionality constant μs, which is called the coefficient of static friction.

and

and  , not the vectors themselves. This equation does not imply that the directions of the vectors are the same. In fact,

, not the vectors themselves. This equation does not imply that the directions of the vectors are the same. In fact,  is parallel to the surface, while

is parallel to the surface, while  is perpendicular to it.

is perpendicular to it.

, has no units. Also, it depends on the type of material from which each surface is made (steel on wood, rubber on concrete,

etc.), the condition of the surfaces (polished, rough, etc.), and other variables such as temperature. Table 4.2 gives some typical values of μs for various surfaces. Example 9 illustrates the use of Equation 4.7 for determining the maximum static frictional force.

, has no units. Also, it depends on the type of material from which each surface is made (steel on wood, rubber on concrete,

etc.), the condition of the surfaces (polished, rough, etc.), and other variables such as temperature. Table 4.2 gives some typical values of μs for various surfaces. Example 9 illustrates the use of Equation 4.7 for determining the maximum static frictional force.

has three main characteristics, to a good degree of approximation. It is independent of the apparent area of contact between

the surfaces (see Figure 4.21). It is independent of the speed of the sliding motion, if the speed is small. And lastly, the magnitude of the kinetic frictional

force is proportional to the magnitude of the normal force. Equation 4.8 expresses this proportionality with the aid of a proportionality constant μk, which is called the coefficient of kinetic friction.

has three main characteristics, to a good degree of approximation. It is independent of the apparent area of contact between

the surfaces (see Figure 4.21). It is independent of the speed of the sliding motion, if the speed is small. And lastly, the magnitude of the kinetic frictional

force is proportional to the magnitude of the normal force. Equation 4.8 expresses this proportionality with the aid of a proportionality constant μk, which is called the coefficient of kinetic friction.